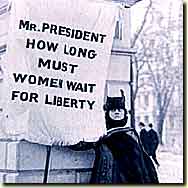

Throughout the winter of 1917, Alice Paul and her followers in the National

Women's Party picketed the White House. They stood silently at the gates,

holding signs that said "Mr. president, how long must women wait for liberty?" The picketers

were suffragists. They wanted President Woodrow Wilson to support a

Constitutional amendment giving all American women suffrage, or the right to

vote.

At first, the suffragists were politely ignored. But on April 6, 1917, the

United States entered World War I. The suffragists' signs became more pointed.

They taunted Wilson, accusing him of being a hypocrite. How could he send

American men to die in a war for democracy when he denied voting rights to

women at home? The suffragists became an embarrassment to President Wilson. It

was decided the picketing in front of the White House must stop.

At first, the suffragists were politely ignored. But on April 6, 1917, the

United States entered World War I. The suffragists' signs became more pointed.

They taunted Wilson, accusing him of being a hypocrite. How could he send

American men to die in a war for democracy when he denied voting rights to

women at home? The suffragists became an embarrassment to President Wilson. It

was decided the picketing in front of the White House must stop.

Spectators assualted the picketers, both verbally and physically. Police did

nothing to protect the women. Soon, the police began arresting the suffragists

on charges of obstructing traffic. At first, the charges were dropped. Next,

the women were sentenced to jail terms of just a few days. But the suffragists

kept picketing, and their prison sentences grew. Finally, in an effort to break

the spirit of the picketers, the police arrested Alice Paul. She was tried and

sentenced to 7 months in prison.

Paul was placed in solitary confinement. For two weeks, she had nothing to eat

except bread and water. Weak and unable to walk, she was taken to the prison

hospital. There she began a hunger strike--one which others would join. "It

was," Paul said later, "the strongest weapon left with which to continue... our

battle . . ."

Paul was placed in solitary confinement. For two weeks, she had nothing to eat

except bread and water. Weak and unable to walk, she was taken to the prison

hospital. There she began a hunger strike--one which others would join. "It

was," Paul said later, "the strongest weapon left with which to continue... our

battle . . ."

In response to the hunger strike, prison doctors put Alice Paul in a

psychiatric ward. They threatened to transfer her to an insane asylum. Still,

she refused to eat. Afraid that she might die, doctors force fed her. Three

times a day for three weeks, they forced a tube down her throat and poured

liquids into her stomach. Despite the pain and ilness the force feeding caused,

Paul refused to end the hunger strike--or her fight for the vote.

By the time Alice Paul was sent to prison, the fight for women's suffrage had

been going on for almost 70 years. It had started in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New

York, at a small Women's Rights Convention. These early feminists wanted the

same opportunities as men. They wanted the chance to attend college, to become

doctors and lawyers, and to own their own land. If they could win the right to vote,

they could use their votes to open the doors of the world to women.

By the time Alice Paul was sent to prison, the fight for women's suffrage had

been going on for almost 70 years. It had started in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New

York, at a small Women's Rights Convention. These early feminists wanted the

same opportunities as men. They wanted the chance to attend college, to become

doctors and lawyers, and to own their own land. If they could win the right to vote,

they could use their votes to open the doors of the world to women.

For the next 50 years, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony led the

women's rights movement. Thanks to their efforts, the women's suffrage

amendment was presented to Congress for the first time in 1878. But Congressmen

refused to allow a vote on the issue. The amendment was reintroduced every year

for forty years. During that time, it was never voted upon.

By the time Alice Paul and the National Women's Party began their suffrage

campaign, the old leaders of the women's movement were gone. But support for

the suffrage amendment had grown. Women were already voting in twelve western

states. And in 1916, Jeannette Rankin of Montana became the first women elected

to Congress. Yet Congress was no closer to passing the suffrage amendment than

before.

Paul was a veteran of suffrage protests. She had served a prison term in

Britain for supporting women's right to the vote. She and other younger leaders

like Harriet Stanton Blatch thought one last push was needed to get the

attention of the President and the Congress. Giant suffrage parades were held

in New York and Washington. Thousands of suffragists in long white dresses

marched. There were floats, women on horseback, and banners flying. A number of

men joined in. But the parades did not change the minds of President Wilson or

Congress. So the picketing began at the White House.

Paul was a veteran of suffrage protests. She had served a prison term in

Britain for supporting women's right to the vote. She and other younger leaders

like Harriet Stanton Blatch thought one last push was needed to get the

attention of the President and the Congress. Giant suffrage parades were held

in New York and Washington. Thousands of suffragists in long white dresses

marched. There were floats, women on horseback, and banners flying. A number of

men joined in. But the parades did not change the minds of President Wilson or

Congress. So the picketing began at the White House.

After 5 weeks in prison, Alice Paul was set free. The attempts to stop the

picketers had backfired. Newspapers carried stories about the jail terms and

forced feedings of the suffragists. The stories angered many Americans and

created more support than ever for the suffrage amendment.

Finally, on January 9, 1918, WIlson announced his support for suffrage. The

next day, the House of Representatives narrowly passed the Susan. B. Anthony

Amendment, which would give suffrage to all women citizens. On June 4, 1919,

the Senate passed the Amendment by one vote. And a little more than a year

later, on August 26, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the

amendment. That made it officially the Nineteenth Amendment to the

Constitution.

Finally, on January 9, 1918, WIlson announced his support for suffrage. The

next day, the House of Representatives narrowly passed the Susan. B. Anthony

Amendment, which would give suffrage to all women citizens. On June 4, 1919,

the Senate passed the Amendment by one vote. And a little more than a year

later, on August 26, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the

amendment. That made it officially the Nineteenth Amendment to the

Constitution.

American women at last had the right to vote. But Alice Paul and her colleagues

did not stop their campaign for women's rights. Instead, they began to push for

an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, which would guarantee women

protection against discrimination. Some 80 years later, the battle for such an

amendment is still being fought.

American women at last had the right to vote. But Alice Paul and her colleagues

did not stop their campaign for women's rights. Instead, they began to push for

an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution, which would guarantee women

protection against discrimination. Some 80 years later, the battle for such an

amendment is still being fought.